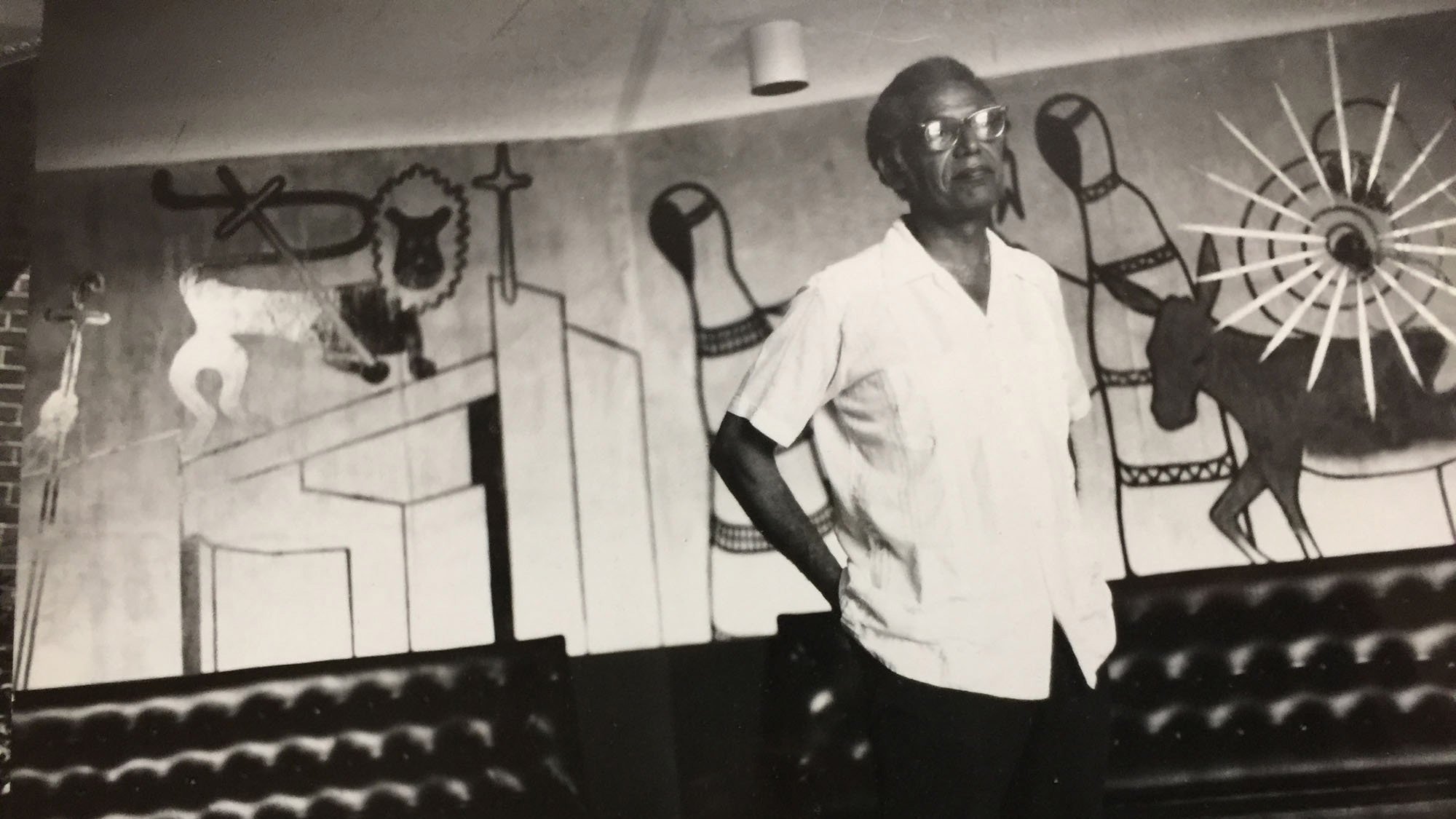

Tuskegee University’s Black Architect, Edward Lyons Pryce

Not long before he died in 2007, Edward Lyons Pryce requested an important favour from his daughter, Marilyn Pryce Hoytt. “Don’t let the world forget about me, Patty,” he said, referring to her by her nickname. It’s a common sentiment at the end of anyone’s life, but it’s an especially difficult task for Pryce Hoytt because there is so much to remember about her father and, until recently, an appalling lack of recognition for this seminal figure in landscape architecture. Pryce’s life and work are gravely understudied.

Edward Lyons Pryce, The Tuskegee Institute’s Black Landscape Architect

Also Read: A Texas Pedestrian Bridge’s Design Expresses Community

He was a black landscape architect born in 1914, as well as a professor, horticulturist, campus planner, preservationist, and artist. He was the first black landscape architect licenced in the United States and the first black fellow of the American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA), and his career was defined by his association with Alabama’s Tuskegee Institute, whose campus he guided, grew, and preserved for more than four decades.

However, renewed interest in Pryce and other black landscape designers has highlighted what landscape architect Glenn LaRue Smith of PUSH Studio refers to as a “blank spot in history.” The Black Landscape Architects Network, which Smith founded, has announced the creation of a new scholarship named after Pryce for black undergraduate and graduate students.

The scholarship is funded by a donation from Pryce’s daughters, Pryce Hoytt and Joellen ElBashir. Smith began a research fellowship at Dumbarton Oaks in January, and Pryce is one of about a dozen black landscape architects he is attempting to document. His goal, he says, is to compile this information into an exhibition that “documents for the first time the work of these black landscape architects—drawings, sketches, and everything else that does not exist anywhere.”

Also Read: LeBron James Innovation Center Blending Modernism With Sport

In response to their exclusion from commercial practice, early Black practitioners gravitated toward strong institutional attachments, such as Tuskegee. Because they were unable to enter traditional firms, Tuskegee, Howard University, and North Carolina A & T were among the HBCUs that produced some of the black landscape architects, he explains.

Pryce was born in Lake Charles, Louisiana, and grew up in Los Angeles. He graduated from Tuskegee University in 1937 with a degree in horticulture. Pryce assisted George Washington Carver in his studies of black subsistence foods such as wild lettuce and dandelion greens, documenting their vernacular use and nutritional value and establishing a theme throughout Pryce’s career of applying disciplinary rigour to horticultural practises born of pure necessity.

Edward Lyons Pryce, The Tuskegee Institute’s Black Landscape Architect

One of the few sources on Pryce’s life is Dreck Spurlock Wilson’s African-American Architects: A Biographical Dictionary, 1865–1945. He earned an undergraduate degree in landscape architecture from Ohio State in 1948, according to Landscape Architecture Magazine, while studying during the day, working at a steel mill at night, and sleeping at a draughty YMCA (LAM).

He continued to earn high honours and was awarded the 1947-48 Certificate of Merit, recognising him as the program’s best student. Nonetheless, no one would hire him. Employers recognised his abilities, but clients would simply not be “comfortable” with a black designer, according to Pryce Hoytt.

Also Read: Architects Paritzki and Liani built a triangular white stone house.

As a result, he made his way back to Tuskegee. There he worked alongside David Williston, Pryce’s predecessor in landscape design and the first black landscape architect. Pryce was drawn to him because he “was doing engineering, horticulture, and art,” as he explained to LAM.

He served as superintendent of buildings and grounds and professor at the school of architecture from 1948 to 1977, after which he continued as a consulting landscape architect until 1990. He received an MLA from the University of California, Berkeley in 1953 and became the organization’s first black fellow in 1979, having previously been denied membership due to his race.

Very few people have had as much influence on the Tuskegee campus as Pryce, and his work as a landscape preservationist is likely his greatest legacy. He wrote the grant proposal that resulted in the Tuskegee campus being nominated as a National Historic Site in 1972 (the same year he became the first black landscape architect to earn a professional licence).

Today, Tuskegee is the only historically black college or university to be designated a National Historic Landmark and to offer a programme of study in historic preservation. “We credit him for everything,” says Kwesi Daniels, interim dean of Tuskegee University’s architecture school. As a preservationist, Pryce painstakingly recreated Williston’s planting and paving plans, as well as historical maps of the campus, and his work continues to guide Tuskegee’s preservation today.

Edward Lyons Pryce, The Tuskegee Institute’s Black Landscape Architect

One of Pryce’s most lasting legacies is his documentation of the Tuskegee campus’s singular pedagogy. Since Booker T. Washington’s founding, the school has focused on teaching students discrete, marketable trades segregated by gender rather than broad areas of knowledge embodied in a degree.

The men acquired skills as wheelwrights, carpenters, and masons, and the students used these abilities to construct the campus. Women learned to sew, make mattresses, and a variety of other skills. Due to black people’s limited access to capital and land, their best chance of escaping the day’s enforced racial and economic hierarchy was to compete at the highest wage level possible, and this philosophy drove the campus’s development.

Buildings were grouped according to trade rather than a degree programme, a practice that persisted during Pryce’s tenure, as evidenced by the grouping of the nursing school, the school of veterinary medicine, and the hospital. When Pryce documented the campus, he laid the groundwork for recognising our campus’s uniqueness and the fact that students not only built the buildings, but also the bricks that went into them, Daniels explains. Tuskegee was constructed using bricks, timber, and labour sourced locally. “You’re discussing sustainability before there was such a thing,” he says.

According to Tuskegee’s 2009 Campus Heritage Plan, Pryce was meticulous in incorporating existing trees into new landscape designs, preserving soil islands around trees located in parking lots. He placed a premium on boulevards and formal courtyards, relegating parking lots to the site’s periphery and occasionally concealing them with hedges. His walkways, like his plantings, tended toward graceful arcs. “He would never plant anything straight,” Pryce Hoytt explains.

According to Daniels, Pryce favoured subtly aligning landscapes with existing topography (a possible influence from Williston), as evidenced by his “soft-terraced spaces” at Paul Rudolph’s Tuskegee Chapel.

One of Pryce’s most persistent challenges was maintaining the campus on a shoestring budget, and he devised ingenious workarounds, some of which are now considered standard landscape practice. In the campus greenhouse, he grew all of the flowers used in graduation ceremonies. He and his landscape crews would harvest trees and shrubs from nearby forests, grafting them into his designs; hyper-native ecologies are now the low-maintenance, low-carbon default for many designers. According to Pryce Hoytt, her father “adored everything that was natural to Alabama.”

According to Daniels, Pryce’s commitment to Tuskegee meant “not using a lack of funding as an excuse for not achieving excellence, but recognising that excellence is necessary.”

Due to a simple lack of resources, Smith and his colleagues at the Black Landscape Architects Network focused their efforts on scholarships as well. As a former chair of the landscape architecture department at Baltimore’s Morgan State (another HBCU), he knows that the primary barrier to entry for many black students is not talent or ability, but cost. The Edward Lyons Pryce Scholarship will award two $2,000 scholarships to black undergraduate and graduate students, respectively.

I would attract students who desired to attend, but because it was a graduate programme, the majority of them were slightly older, had families, and we were juggling work and school, and I never had the resources to assist them with two or three credits of courses. As a result of our discussions with the board, we determined that it was critical to increase the number of black landscape architects in the profession by supporting students enrolled in programmes. ” The scholarship recipient will be announced later this month.

Written By Tannu Sharma | Subscribe To Our Telegram Channel To Get Latest Updates And Don’t Forget To Follow Our Social Media Handles Facebook | Instagram | LinkedIn | Twitter. To Get the Latest Updates From Arco Unico